During the execution of a work there are several events that can result in negative impacts and delays to the project schedule, and sometimes these different events overlap over a period of time in the same activity. If the delays are caused by both the owner and the Contractor, and affect the same activity or parallel activities that have no delay on schedule, both are equally critical and the parties have responsibility for the delay. This is a complex, controversial technical and legal issue that we call “Concurrent Delay”. On the one hand, the challenge is to determine fairly the Contractor’s right to extend the term as a result of a delayed event of the Contractor’s liability and to reimburse the additional costs with that extension. On the other hand, considering events under the Contractor’s responsibility, there is a need to make up for the delay or indemnify the owner due to the failure to complete the work within the agreed time.

Each delay must be verified along the critical path of the “as built” schedule (as done), have its cause identified and must be independently quantified. For that, first, it is necessary to identify and understand the contractual clauses pertinent to the occurrence of delays in order to determine the compensable and justifiable character. When contractual clauses are subjective in determining competing delays, the following internationally recommended practice is:

1- Compensable Delay: These are delays by the owner that postpone the final project date. These delays were not competing with delays for which the Contractor is liable or with delays resulting from force majeure events. In this case, the Contractor is entitled to a term and to reimburse additional costs;

2 – Justifiable Delay: Delays caused by the owner, or caused by events of force majeure, which were competing with events of delay of the Contractor or events of force majeure, and which delayed the final date of the project. In this case, the Contractor is entitled to terms, but is not entitled to economic compensation for the term extension. Penalties are not applicable by the owner;

3- Unjustified Delay: These are delays for which the Contractor is liable, and for this reason it has an obligation to make efforts to recover them, and / or may be penalized.

Premises for identifying competing delays

The delays in a Construction are shown from the perspective of the side on which the analysis is located. The Contractor seeks to demonstrate that the delay is compensable for the competition period if these delays are only overlapped for a period, or even, that the delay is justified, using the competing delay as an element to avoid penalties established in the contract.

on the other hand, the owner uses the concurrent delay to deconstruct the Contractor’s claim for compensable delay, converting it to justifiable or even unjustifiable delay. Thus, for alignment, some of the best known guides in the field of forensic construction analysis, the “Society of Construction Law” (“SCL”) and the “American Association of Cost Engineering (“ AACE ”), guide to the characterization and the calculation of Concurrent Delays.

Regardless of which side the analyst is working on, there are four prerequisites necessary for the delay to be considered concurrent:

- There must be two or more independent delays and be on the critical path of the project;

- Delays must be caused by different parties or by force majeure events;

- The delay or deceleration of activities must be involuntary;

- -The event must be proven to be difficult to solve.

The AACE protocol 29R-03 describes in detail the four prerequisites, however, the authors consider it important to make two considerations: (i) In relation to events of force majeure, some contracts treat this type of delay as compensable, so if the The contractor has its own concurrent delay with a compensable force majeure event, it may be entitled to a compensable delay instead of being justified; (ii) During the execution of the project there may be periods with many delays that are concurrent, but not all will be on the critical path (probably one will be). The Contractor, upon demonstration, may be entitled to the costs associated with delays in non-critical activities.

Typical Scenarios of Concurrent Delays

There is a conception that competing delays are two independent delays impacting the critical path in the same period of time. However, as the following scenarios show, competing delays have variants that determine the type of delay to be considered.

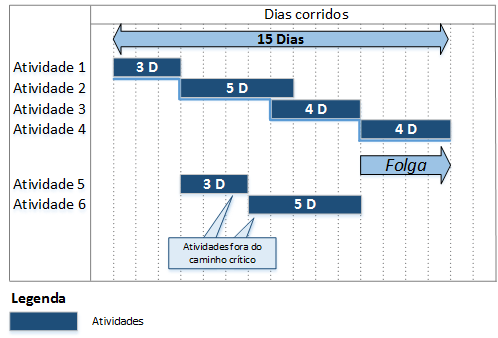

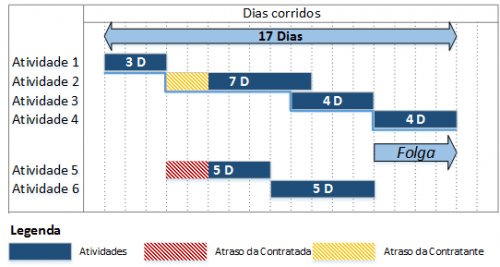

In order to further illustrate the different scenarios, a simple hypothetical schedule with a total duration of 15 days was considered, with a critical and a non-critical path.

The following analysis scenarios are presented below:

Scenario n°1

This scenario is known as a true concurrent delay. It consists of two independent delays, one by the Contractor and the other by the owner, which impacted the critical path and have the same duration of two days. In this case, the Contractor is normally entitled to an extension of the term for the competing delay, but is not entitled to economic compensation. (Justifiable delay).

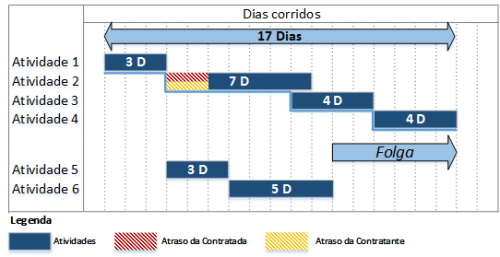

Scenario n°2

Scenario 2 shows two independent delays, one caused by the Contractor and one by the owner, impacting the critical path in two days. However, the owner’s delay is greater than that of the Contractor in one day. In this case, the Contractor is normally entitled to a delay justified by the part of the delay that is concurrent (in this case, 1 day), and to the delay compensable by the part of the delay that is the responsibility of the owner only (in this case, 1 day).

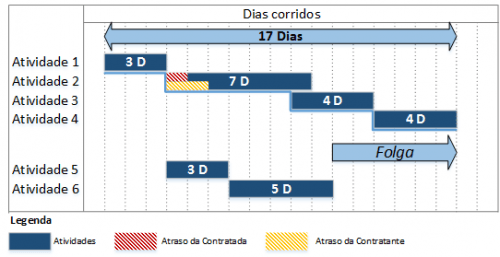

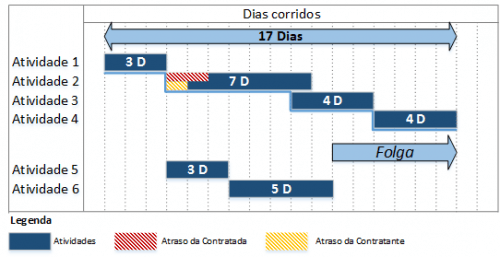

Scenario n°3

Similar to scenario 2, this scenario shows two independent delays with different durations impacting the critical path. In this case, the Contractor’s delay is greater than that of the owner in one day. Thus, the Contractor may be entitled to extend the term (justifiable delay) for the delay that is concurrent (in this case, 1 day). However, the Contractor may be susceptible to penalties for the part of the time in which it was only responsible for the delay.

Scenario n°4

Scenario 4 shows two independent delays: one on the critical path and the other on a non-critical path. Although technically it is not considered a concurrent delay. since, the delay in the critical path is eliminated, the other delay will not impact the project’s completion. The authors consider it important because this type of situation is usually neglected during the schedule analysis of the project. This case shows two events occurring concurrently, the Contractor is delaying the critical path of the project, while the owner is impacting another non-critical activity. In this case, the Contractor is susceptible to penalties for delay as it affects the completion of the project (not justified). However, the Contractor may be entitled to specific additional costs related to the delay in non-critical activity caused by the owner.

Scenario n°5

Similar to scenario 4, it depicts two delays, one impacting a critical activity and the other impacting a non-critical activity, which are occurring during the same period of time. The difference with scenario 4 is that the event impacting the critical path is caused by the owner therefore, the Contractor may be entitled to the extension of time and indirect costs associated with the delay (compensable). In the case of the event impacting a non-critical activity, caused by the Contractor, the owner normally is not able to apply penalties for the delay for not being inserted in the critical path. However, if the non-critical activity is linked to a mandatory framework (which contractually establishes penalties for delay), the Contractor is susceptible to penalties.

Pacing Delay

What differentiates the “Pacing Delay” from a competing delay is that a party, usually the Contractor, consciously slows down or even stops work due to a delay caused by the other party. As already mentioned, one of the prerequisites to be considered a concurrent delay is that it must be involuntary, and in the case of the “Pacing Delay” the affected party voluntarily and consciously slows down the work, in order to mitigate probable economic damage in the future.

A typical case is when the owner delays obtaining a license to work in an area where a critical activity will take place, and then the Contractor decides to slow down the work while the owner solves the problem. The deceleration may be in the form of retaining mobilization, or relocating resources to other work areas where they can be used. Another typical case is related to the lack of projects under the responsibility of the owner, or their extemporaneous review.

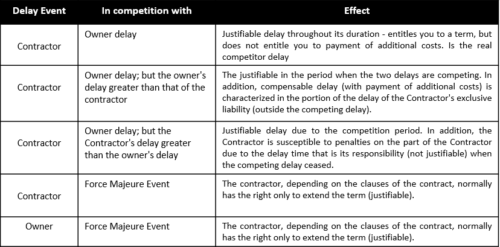

Delay Attribution

The following table presents the situations of delays and their effects in each specific situation.

In conclusion, concurrent delays are real and the subject of discussion in most schedule analyzes. However, the analysis of competing delays has several situations, been poorly performed, which has led not only to court rejections also, to the overall results of the schedule analysis. Thus, what is exposed in this article is intended to clarify how this topic is guided by respected institutions that study additional costs in construction and practiced in the courts for resolving conflicts involving engineering contracts.

Geovane Mendes Martins Director da Hormigon Hect geovane@hect.com.br Geovane Martins is a partner at Hormigon Hect and has over 20 years of experience in the field of engineering and contract administration, notably in project management processes, people management, and consulting in the preparation of Claims. He currently provides consultancy work in project and contract management for the pulp, energy and mining industry in Brazil and Argentina (contractors), as well as consulting in the preparation of claims for construction companies and assemblers. He also acts as a technical assistant in demands in the judiciary and in arbitration chambers, supporting law firms. Luis Edgard Roman Director lroman@navigant.com